Introduction #

This blog post aims at giving a crash course in this huge domain of computer science that is concerned with compilers for programming languages. All our examples will be taken from the Kotlin programming language. Let’s get started because we have a lot of ground to cover! I hope you enjoy this introduction to such an interesting topic.

What is a Compiler? #

Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools, also known as the Dragon book, defines a compiler as the following:

Simply stated, a compiler is a program that can read a program in one language — the source language — and translate it into an equivalent program in another language — the target language.

In most cases, the target language is machine code — we want to run our program written in a human-readable source language on a computer; the thing is that computers can only understand machine languages.

So we need a program that can process a sequence of words and sentences, written in some source language that must be well-defined — which means that there is a grammar and rules to determine how words from the grammar can be composed in a way that has a valid meaning in that language.

It’s intriguing to note that this has a lot of parallels with how we as humans learn natural languages: the English language has a set of valid words that composes its grammar and rules that define what is a semantically valid sentence in the language.

Then, we must be able to execute a sequence of steps that, in the end, gives us some sequence of words and sentences in the target language, but with the guarantee that it has the same meaning as the source. We’ll see that there are a lot of intermediate steps that compilers take before it can return this target language.

Frontend #

The frontend of a compiler deals with defining the structure and meaning of the source language. This analysis is done in several steps that will be covered in the next sections.

Lexical Analysis #

In this step, a Lexer iterates over all characters in the source code and classifies every word as a token type that is predefined for the source language. Take the following token types extracted from the Kotlin compiler KtTokens.java:

| Token Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| LBRACKET | [ |

| RBRACKET | ] |

| PLUSPLUS | ++ |

| ELVIS | ?: |

| SUSPEND_KEYWORD | suspend |

| WHEN_KEYWORD | when |

So for every possible sequence of characters in a source language, there must exist some Token Type associated with it. If the Lexer cannot find a Token Type for a given sequence of characters, the compilers will throw an error indicating that the source contains invalid characters — I’m sure you have experienced some of these errors!

For an output example of a lexer, take the following code snippet in Kotlin:

suspend fun foo() {

val hello = "Hello, World!"

}

A lexer would return something like this:

SUSPEND_KEYWORD FUN_KEYWORD WHITE_SPACE IDENTIFIER(foo) LPAR RPAR WHITE_SPACE LBRACE

WHITE_SPACE IDENTIFIER(println) LPAR REGULAR_STRING_PART ("Hello, World!") RPAR

WHITE_SPACE RBRACE

Notice that it classified every character as a valid token. Additionally, a lexer adds even more information to each token, such as the column and line where the token was found — this is important to be able to report errors precisely, knowing exactly in the file an error occurred. This representation of source code allows making further analysis, as we’ll see in the next section.

Syntax Analysis #

Just as in a natural language, you can use valid words and create sentences that are not correct by the rules of the language grammar. The same is true in the context of compiler language translation: each programming language must have a set of grammar rules that are used to analyze the syntax of any given source language. The grammar uses the language Token Types to compose valid sentences; by using the result from lexical analysis, it is possible to validate if the source language conforms to the grammar.

Programming languages grammars are normally described as Context-free Grammars (CFG), and here we can see a crossover between Linguistics and Computer Science — CFGs are used in both fields. A common notation for programming languages CFGs is the Backus-Naur form (BNF). Take a look at the Syntax Grammar for Kotlin; it follows the BNF.

Parser #

This is a pattern that repeats during most compiler phases that we will look at — we start with a given structure of the source code and apply transformations, changing the structure to suit the objectives of the current phase. In this case, we use a Parser, generated from the syntax grammar, to create an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). The AST is a representation of the source code that can be reused by later stages of the compilation. It is abstract in the sense that it contains only the structure of the grammar phrases in the source code, but removes everything that was used to infer that structure during the syntax analysis phase.

Semantic Analysis #

Knowing that a source file conforms with the syntax of a language is not enough — again, you can be syntactically correct and create phrases that have no meaning! This follows for programming languages. So the compiler needs to make a semantic analysis after the syntax analysis phase.

Understanding the semantic meaning of a language is a lot harder, though. Normally, semantic errors are syntactically correct. Semantic errors are errors related to the behavior of the program. Examples of semantic errors are returning a different type than was defined in a function signature; using variables that are out of the scope of the current execution; trying to sum variables of incompatible types.

So there must be some kind of structure that facilitates this analysis — the AST obtained in the previous stage is used for this purpose. We will traverse the AST from its root and at each step, record information about the different variables, functions, and types that are used. We store this information in a Symbol Table. By analyzing the symbol table, the compiler can check for semantic errors such as the ones described above.

For example, when your IDE tells you that you’re trying to use an out-of-scope variable, it is performing some kind of semantic analysis.

Intermediate Representation (IR) #

With the source code analysis complete, the compiler can guarantee that there are no errors in the source program, and it finally starts the process of translating this source language into the target language.

The final step in the frontend of a compiler is translating the AST into an Intermediate Representation that is better suited for the types of operations that the backend of the compiler needs to execute.

It is important to note that, conceptually, we have seen a lot of IRs up until now; we could call the AST some kind of intermediary representation for the frontend. But normally, an IR is a structure that is passed from the frontend to the backend of the compiler. So, whenever we talk about IR in this context, we will be talking about operations and steps that are executed in the backend.

What exactly is the utility of this IR, then? Well, there are a lot of possible target languages that some source programming language may need or want to compile to. Each computer architecture has its own kind of machine language — x86 is different from ARM, that is different from RISC-V. Which means that having a common IR helps in reducing the number of full compilers that need to be built.

This is the reason that compilers are split in frontend and backend — we can have 1 frontend that generates a common IR that is used by N backends, where each one of them translates our source language to a different target (machine) language. LLVM is probably the most prominent project in this space. If you create a programming language that can generate LLVM IR, you can use the LLVM backend to translate your language to a multitude of computer architectures.

Backend #

The backend then takes an Intermediate Representation generated on previous steps and applies code transformations. Some of these transformations which aim to optimize code include data-flow analysis, such as:

- Dead code elimination: removing unused variables;

- Common subexpression elimination: removing calculations of a repeated expression;

- Constant folding: calculating constant expressions at compile-time;

- Register allocation: reuse of registers during code execution;

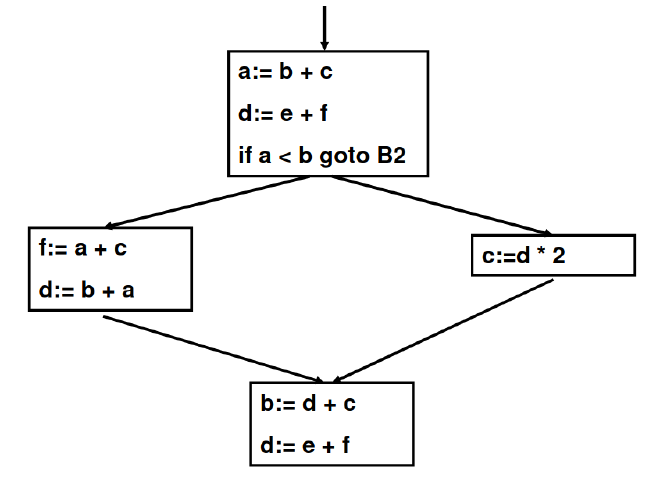

A Control-flow graph is often used to apply data-flow analysis, since it gives a representation of code in basic blocks, where each block contains all code instructions between control flow instructions. An example would be the following image:

These code transformations on an initial Intermediate Representation are called lowering phases. Each new transformation brings the code representation closer to its target machine language.

LLVM #

We cited LLVM previously, but it does deserve more information. The LLVM project is “a collection of modular and reusable compiler and tool chain technologies”, as their website denotes. It is a leading backend compiler optimizer that offers code generation for many popular CPU architectures.

This is a good reason for having separate representations for a compiler frontend and backend are important - you can, for example, create a new language and develop a compiler frontend that, at the end, generates LLVM IR and automatically support multiple architectures. It makes compilers composable and decoupled; creating state-of-art optimizations for multiple CPU architectures is a lot of work; leveraging the open-source community for that can be a very good decision.

Putting it all together: Kotlin compiler diagram #

Now we can take a look at a real compiler diagram and identify its parts with a little more familiarity. We will be taking a look at the Kotlin compiler and how it evolved over time, as well as some interesting Intermediate representations that JetBrains opted to use in the first iteration of the compiler.

Frontend #

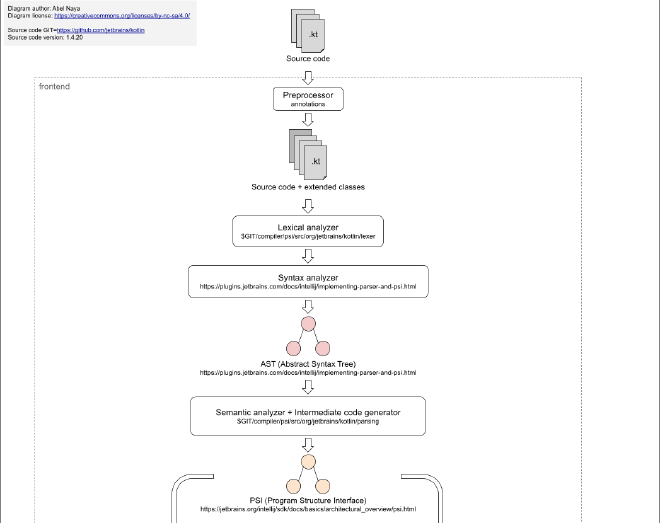

In the diagram below we can see that the frontend for the Kotlin compiler follows a similar structure from what we have seen with some additional phases.

For example, at the start of the compilation process, the compiler executes preprocessor annotations; this allows the creation of Kotlin code at the start of the compilation process. This is where KSP or KAPT would come in. Any library that uses annotations to generate boilerplate code has that code generated before any actual compiler phases starts. Check out compose-destinations for an awesome example in the Jetpack Compose ecosystem.

Apart from that, there is the Program Structure Interface that is the Intermediate Representation that JetBrains chose to use for the Kotlin compiler. The PSI is an IR created by JetBrains to be used in its IntelliJ Platform. It is the PSI that powers JetBrains IDE features such as code completion, refactoring, navigation, inspection, and a lot more.

It is in a way an IR for JetBrains IDEs, allowing the creation of tools without having to rely on an implementation for each programming language that JetBrains supports. If there is a PSI representation of a programming language, a lot of IDE tools can be automatically used. Think of it like a common interface for these features.

So it is a logical choice to leverage an existing technology that is mature and well understood by JetBrains employees and, most likely, has a lot of support in libraries, internal tools and the like.

This is interesting to make the point that compilers are software projects just like all other software projects; they are bound to the same design, architecture, and feature implementation decisions that we make in our own domains. This is an example of that: choosing PSI makes sense from a practical sense for JetBrains, and probably allows for better integration with the IntelliJ Kotlin plugin.

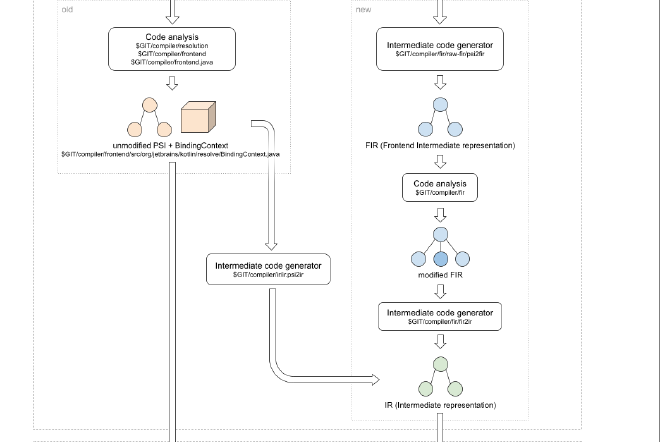

From here, we can see that the diagram shows two different steps: let’s call them first (old) and current (new) iteration. At its first iteration, the PSI IR was passed as is to the compiler backend along with a data structure called BindingContext that held the semantic information for the code.

In its current iteration, there are a lot of new phases run on the code, transforming the PSI into another intermediate representation called a Frontend Intermediate Representation (FIR) before it reaches the backend. More phases are applied to the FIR and, finally, it is transformed into the IR that the backend will use.

This new architecture called K2 allows for more flexibility and the addition of new phases both in the frontend and backend of the compiler.

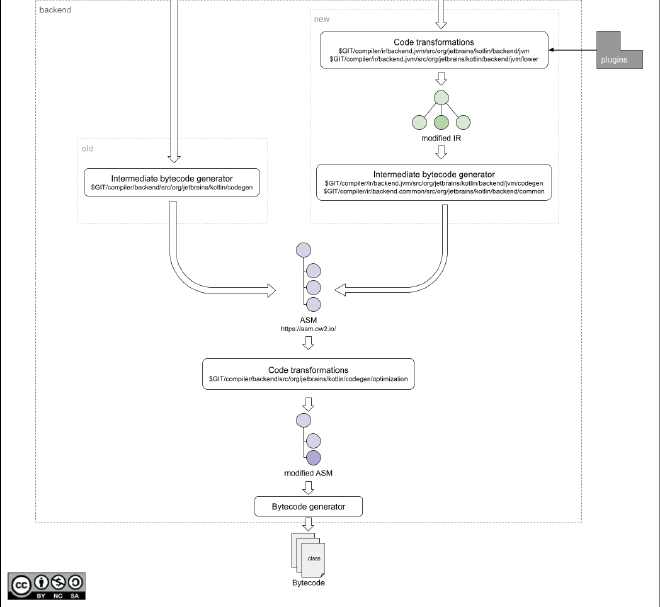

And as we can see in this last diagram, another round of transformations or, since we are in the backend, lowering phases, takes the IR and modifies it before applying even more code optimization phases for the given target, in this case changing the IR to a bytecode representation since the diagram shows the JVM target.

Compiler plugins #

The Kotlin compiler allows developers to create plugins both in the frontend and backend of the compiler.

These plugins can modify the compiler IR in different stages of compilation; for example, a frontend compiler plugin is able to extend the Kotlin Type System or emit compile-time custom errors and warnings.

A backend plugin is harder to develop, since it deals with an IR that is a lot more low-level than its frontend counter-part. But it can be useful — for example, the

all-open compiler plugin has widespread use in Spring projects. It modifies the default behavior of Kotlin classes and members from being final by default to open.

Compiler plugins are powerful tools that can be used to adapt a compiler to suit application developers needs, but are definitely a niche tool by definition.

Wrapping up #

I hope you enjoyed this introduction to Compiler Architecture! It is a complex topic to cover, but one that I really wanted to learn more about. It was specially interesting to delve in the Kotlin compiler implementation and see how a real full-fledged compiler is built. I encourage you to take a look at the source code for the Kotlin compiler — it is less intimidating than it looks!

Until next time!

References and additional material #

- discussions and diagrams about the Kotlin compiler part 1

- discussions and diagrams about the Kotlin compiler part 2

- Kotlin Compiler Internals

- What Everyone Must Know About The NEW Kotlin K2 Compiler

- Kotlin Compiler Crash Course repository

- Exploring Kotlin IR blog post

- Kotlin Power Assert - a Kotlin compiler plugin

- K2 Compiler plugins by Mikhail Glukhikh

- all-open compiler plugin