An introduction to Coding Agents

What are Coding Agents?

Definition

A software that allows interaction with LLMs and chains calls (or, put another way, a conversation), maintaining a specific context and enabling the use of tools to expand the conversation's context and, furthermore, allow the LLM to create, modify, and generally interact with the system in question.

Anthropic defines it as follows:

Systems where LLMs dynamically direct their own processes and tool usage, maintaining control over how they accomplish tasks.

Simon Willison has a concise definition that, in my opinion, synthesizes the concept very well:

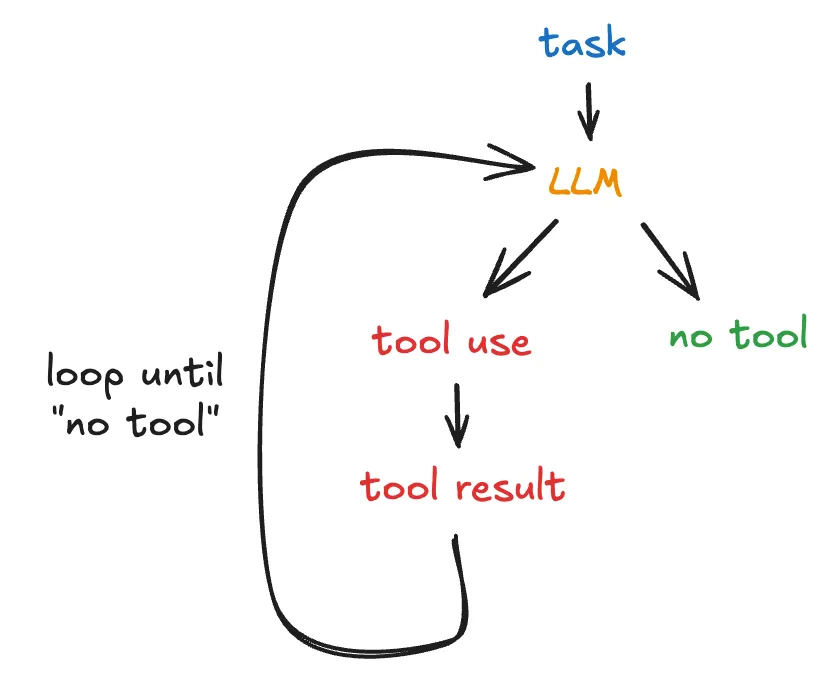

An LLM agent runs tools in a loop to achieve a goal.

In other words: the LLM is essential for an agent, but alone it is not sufficient: a series of components are needed to expand and allow interaction between the LLM and the available system. It's not the LLM that actually uses the tools - this is done by the software (or agent) that interacts with the LLM. This distinction is very important - the response from an LLM that has tool definitions in its call provides the indication of which tools can be invoked. But actually enabling and executing that invocation is the responsibility of the software that is coordinating these interactions between LLMs and users. Understanding this allows us to see that there's a lot of flexibility in how to use these interactions.

Speaking specifically about coding agents, an intermediary is needed to provide access to the file system, to enable invoking terminal commands like cat, grep, touch, or even to run tests and add these results to the context window. Without this, the LLM's responses, which in this case are code modifications, wouldn't be applied to the system.

What can an agent do?

An agent is, in its essence, a software program like any other. This means it can perform any task that common software can do; the differentiator is the purpose of this software: using its capabilities to manage some functionality that needs to interact with LLMs. The object of study in this article is the subset of agents focused on programming tasks, but this concept extends to any type of agent.

Based on the definition given by Will Larson, we have at least four important capabilities of an agent:

Use an LLM to evaluate a context window and obtain a result

This is the primary use of an LLM - send a certain context that encapsulates the user prompt, tool definitions, tool responses, all the conversation history up to that point, and receive a result from what was evaluated based on that context.

Use an LLM to suggest relevant tools for the current context and, with this use, expand the context window;

APIs like Anthropic's and OpenAI's allow an agent to explicitly provide the set of tools that are available to the LLM in question; with this, all calls to the API include this set of tools and are available to be suggested by the LLM's own response. If used, the result of using that tool can be included in the context window and sent to be evaluated by the LLM.

Manage the control flow of these tools following some business rule or statistical data;

Here we have a use that is possibly more complex. Note that we defined an agent as a software program that makes calls to an LLM API providing a specific context window and access to a set of tools.

Being a software program, we can create rules that define how these interactions are made. For example: imagine that a specific tool has a relevant cost every time it's called. The agent, which is a program, can limit the use of this tool by the LLM, even if its use is suggested.

We can also understand that human intervention or approval is necessary given some response or tool call from the LLM - this is called a human-in-the-loop workflow.

In other words, we can create complex flows by defining business rules that shape how these interactions between LLM and users happen using the agent as an intermediary.

Agents are software programs, therefore they can do anything a common program can do.

The other capabilities make clear the meaning of this capability: without access to functionalities of the system intended to be modified, an LLM cannot perform complex tasks.

High-level operation

An agent uses an execution loop to interact with the LLM:

- Makes calls to the LLM with a prompt, tools, and available context;

- Receives a result from the LLM, possibly indicating the use of a tool;

- Using the tool, returns to the LLM the context added to the result of using the tool;

- If the LLM returns a result without indicating a next step using a tool, returns the result and awaits user input.

LLMs can learn new tasks from examples given in the context of prompts, a capability known as in-context learning (ICL), which is defined by LLMs learning to perform tasks at inference time by following examples provided as context directly in their prompt, without changes to their training. This becomes quite clear when using coding agents and providing code examples to be followed.

This agent feedback loop has proven very important for improving LLM responses associated with ICL.

https://files.cthiriet.com/assets/blog/how-an-agent-works.png

https://files.cthiriet.com/assets/blog/how-an-agent-works.png

Example 1: Anatomy of a LLM API call with tool definitions - Anthropic API

To enable tool calls, we have to send the definitions of these tools as part of all interactions with LLMs - in the case of interactions with Anthropic's API, see how the API behaves:

curl https://api.anthropic.com/v1/messages \

--header "x-api-key: $ANTHROPIC_API_KEY" \

--header "anthropic-version: 2023-06-01" \

--header "content-type: application/json" \

--data \

'{

"model": "claude-sonnet-4-5",

"max_tokens": 1024,

"tools": [{

"name": "get_weather",

"description": "Get the current weather in a given location",

"input_schema": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"location": {

"type": "string",

"description": "The city and state, e.g. San Francisco, CA"

},

"unit": {

"type": "string",

"enum": ["celsius", "fahrenheit"],

"description": "The unit of temperature, either \"celsius\" or \"fahrenheit\""

}

},

"required": ["location"]

}

}],

"messages": [{"role": "user", "content": "What is the weather like in San Francisco?"}]

}'

And a possible response:

{

"id": "msg_01Aq9w938a90dw8q",

"model": "claude-sonnet-4-5",

"stop_reason": "tool_use",

"role": "assistant",

"content": [

{

"type": "text",

"text": "I'll check the current weather in San Francisco for you."

},

{

"type": "tool_use",

"id": "toolu_01A09q90qw90lq917835lq9",

"name": "get_weather",

"input": {"location": "San Francisco, CA", "unit": "celsius"}

}

]

}

The example above was taken directly from Anthropic's documentation: Tool Use Examples

Notice there's an object called tools - here live the definitions of all the tools that can be invoked by the LLM. Each provider has its specific format - in the case of Gemini, for example, tools are called function calls. And in the response, the LLM sends which tool needs to be invoked with the value of its parameters. In this example, we have that the tool get_weather needs to be invoked with location = San Francisco and unit = celsius - something like get_weather("San Francisco, CA", "celsius") would be executed by the software responsible for coordinating these interactions - this is, in fact, the coding agent itself - the LLM API call is just one part of this whole interaction.

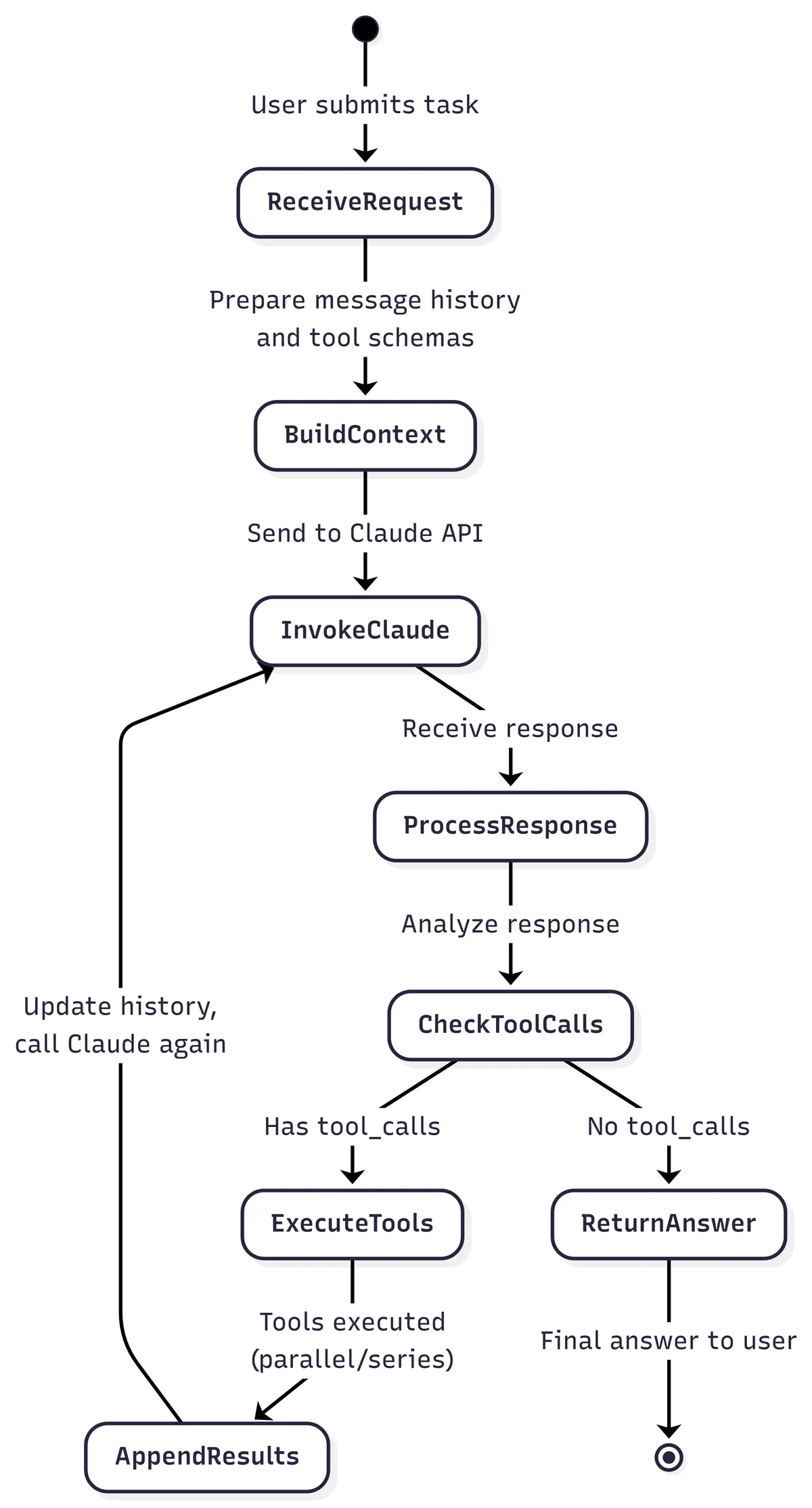

Example 2: Claude Code core loop

Hands-on: Rabbit Coding Agent

The core loop above represents the simplest interaction between the user and LLMs through a text interface. This same core loop is described in the article How to Build an Agent. As part of this exploration of coding agents, I made an implementation based on the article: Rabbit Coding Agent. Compare the diagram above with the following snippet from my implementation:

while (true) {

// Read user input if needed and add to conversation history

if (readUserInput) {

print("\u001b[94mYou\u001b[0m: ")

val userInput = readlnOrNull() ?: ""

conversation.addMessage(userInput)

}

// Send conversation to LLM call and check if response contains tool calls

val response = chatSession.sendMessage(conversation)

val hasToolCall = response.functionCalls()?.isNotEmpty() ?: false

when (hasToolCall) {

// If LLM call wants to call a tool: execute it and add result back to conversation

true -> {

toolCallResult = toolCall(response)

conversation.addMessage(toolCallResult)

}

// If LLM call has final response: print it and wait for next user input

false -> {

println("\u001b[91mRabbit\u001b[0m: ${response.text()}")

readUserInput = true

continue

}

}

// Loop again without reading user input to process tool result

readUserInput = false

}

It's basically a 1:1 implementation of the diagram. I've omitted the tools implementation here, but assume that in all interactions with Gemini, in this case, the definitions of all tools available to this agent are sent. In its response, the Gemini API returns which tools need to be invoked (if there are necessary calls). The heuristic used is that we execute tools until the LLM returns a response without tool calls. At this point, we give control of the session back to the user.

Best practices for agentic coding

System Prompts - AGENTS.md

Define a system prompt with general instructions about code quality, design patterns, useful commands, other documents that can be consulted, specific directives. This file is commonly called AGENTS.md. One way to make this document more efficient in relation to context-window consumption is through managing which information is provided through links to this information in AGENTS.md. This is called progressive disclosure.

Progressive Disclosure

The number of tokens used in an interaction or conversation with coding agents - more commonly called context-window - is an important resource to manage. In complex repositories, there's a lot of information that's important to share for different tasks, but not all of this information is important all the time. For example, knowing about the schema of the relational database tables associated with the repository is important for tasks that modify the data model, but it's not necessary if we're only modifying some business logic that abstracts the data model - in this case, it may be important to read the specifications of these business rules.

In a simplified approach, we can add all this information directly to AGENTS.md: a complete definition of the schema and all business rule specifications. However, this file can grow significantly with each of these additions of situational information.

Therefore, a widely used approach is to briefly describe in which situation that information can be used and indicate the path to another file that will contain the complete information. With this, the LLM itself, equipped with tools to interact with the system, can make the decision of when to read that complete file. In our example, we can have a SCHEMA.md file that contains a complete definition of the tables that make up the data model of the service and a SPECIFICATIONS.md file with relevant business rules.

And the LLM could make the decision to read further instructions for each scenario based on the task at hand based on the reference provided at the AGENTS.md file.

Coding Agents Workflows

There are several types of workflows that can be utilized to extract better responses from the LLM interaction. For this article, I'll provide one example that I find interesting, but in the references section there are links to articles that expand on this topic.

Explore, Plan, Implement, Write Tests:

- Explore: add the necessary context for the task - for example, add only relevant files for the changes that will be made;

- Plan: Request that the LLM make a plan or specification of the changes that will be made. This means asking it to create a step-by-step guide or plan of the changes, tests that need to be created, files that need to be modified; include sufficient details and context. Ensure that the agent won't start implementation before your approval.

- Implement: After your approval of the plan, allow the agent to start implementation

- Write Tests: Ask the LLM to write relevant tests for the implementation it performed. Here it may be worth repeating the Planning step. This step makes sense for components that can be easily tested by unit tests;

Appendix: (Not so exclusive) features of Claude Code

First of all: the features related to adding special prompts in interactions with Claude Code's LLMs are not exclusive to Claude Code. At the end of the day, all that an LLM understands is text. Managing context is an important skill - and these Claude Code features serve to assist in this process. However, they should not be interpreted as magical or exclusive features of this coding agent. Skills, Subagents, Slash Commands, Plan Mode - all of this can be implemented in other coding agents.

Plan Mode

Plan Mode is a read-only interaction mode with Claude Code that is specialized for planning and exploration tasks. In this mode, Claude Code uses tools to explore the codebase and create a detailed execution or implementation plan before implementing any line of code. It's a good way to follow a workflow that has a planning stage like the one mentioned in this article (Explore, Plan, Implement).

Plugins

Plugins are ways to share sub-agents, skills, slash commands, and hooks with other people. A plugin is a package of these other Claude Code features - it's a good way to standardize usage among teams in the same company, for example.

Hooks

Similar to how git-hooks work, Claude Code hooks are commands or scripts that are executed when the corresponding matcher is activated. This matcher is the name or a regex that represents the name of a tool - for example, every time the EditFile tool is invoked, we can execute a script that runs a linter related to the repository's programming language.

It's a way to add validations or deterministic actions every time a specific tool is invoked.

Skills

Skills are prompts that have the following structure within their own directory:

- At least one file called

SKILLS.md, which has markdown frontmatter asmetadatadefining thenameanddescriptionof the Skill, followed by the prompt explaining in detail how to use the Skill itself; - A set of other auxiliary files, whether they are executable scripts or other text files.

It's an extremely simple specification. And, looking closely, it's just another way to manage the context sent to LLMs. Note that the metadata of a Skill is the only part that is always added to the context during sessions with Claude Code. Skills are a clear example of progressive disclosure discussed in this same article.

This format of managing prompts is already being adopted by the industry - OpenAI, Google, and other Anthropic competitors are adding this feature to their coding agents and AI agents in general.

Subagents

Subagents are prompts specialized in some task - for example, creating merge request descriptions based on the current branch. Every time a subagent is invoked, it creates a separate context that is used exclusively for that invocation - therefore, it isolates the context from the conversation that generated that invocation. Similar to Skills, subagent prompts also use markdown frontmatter as metadata. It's another example of progressive disclosure: only the subagent's metadata is sent as part of the context in interactions with the LLM. From this metadata, the LLM makes the decision whether or not to invoke a subagent - these interactions are similar to tool calls, in my understanding.

Custom Slash Commands

Custom Slash Commands are shortcuts for frequently used prompts. There's not much to explain here - the feature is self-explanatory; For example, I have the following prompt that I noticed I use recurrently:

Now, create a merge request description for the current branch using the Merge Request subagent.

Therefore, I created a slash command /mr-description that serves as a shortcut instead of always typing this same prompt. This can be used as a shortcut for much more complicated prompts, of course. Again, note that it's a feature used to manage context.

Conclusion

This sums up what I gathered during my informal research on the topic of coding agents. This is, of course, only a brief introduction to what constitutes a coding agent. But I hope it helped clear up some misconceptions - as a Software Engineer, I feel that it's important to look under the hood and understand, at least conceptually, how these new paradigm-shifting technologies work.

References

This article is the result of an exploration of what defines coding agents for my own learning purposes. So, here is a list of materials that inspired the article:

- https://ampcode.com/how-to-build-an-agent

- https://lukebechtel.com/blog/vibe-speccing

- https://simonwillison.net/2025/Jun/29/how-to-fix-your-context/

- https://simonwillison.net/2025/Jun/27/context-engineering/

- https://simonwillison.net/2025/Jul/3/sandboxed-tools-in-a-loop/

- https://simonwillison.net/2025/Sep/18/agents/

- https://lethain.com/what-can-agents-do/

- https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/function-calling?api-mode=responses

- https://arxiv.org/html/2408.02479v2

- https://github.com/augmentedcode/augment-aider/blob/main/docs/architecture-flow.md

- https://lethain.com/our-own-agents-our-own-tools/

- https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/building-effective-agents

- https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/claude-code-best-practices

- https://arxiv.org/html/2505.19443

- https://www.llamaindex.ai/blog/context-engineering-what-it-is-and-techniques-to-consider

- https://manus.im/blog/Context-Engineering-for-AI-Agents-Lessons-from-Building-Manus

- https://openai.github.io/openai-agents-python/context/

- https://github.com/coleam00/context-engineering-intro

- https://cthiriet.com/blog/nano-claude-code?utm_source=tldrwebdev

- https://github.com/microsoft/ai-agents-for-beginners

- https://anthropic.skilljar.com/claude-with-the-anthropic-api

- https://platform.claude.com/docs/en/agents-and-tools/tool-use/overview

- https://www.anthropic.com/research/in-context-learning-and-induction-heads

- https://platform.claude.com/docs/en/agents-and-tools/tool-use/overview#tool-use-examples